The Baltic Sea Transparency Cooperation aims to strengthen connections between organizations working for protection of the Baltic Sea.

International conference in Tallinn to discuss environmental issues of the Baltic Sea

An international conference will be held in Tallinn on Friday, October 21 focusing on the current situation of the Baltic Sea, the causes of pollution and the possibilities to improve the situation.

“Baltic Sea Transparency Conference” provides an overview of the situation, strategy and national defence of the Baltic Sea.

The conference also includes a panel discussion on the scope and causes of pollution in the Baltic Sea—the participants will be Georg Martin, professor of marine biology at the Estonian Maritime Institute; hydrobiologist Katarina Viik, scientific adviser to the Ministry of the Environment; biologist and conservationist Aleksei Lotman from the Estonian Nature Foundation, and hydrogeology engineer Arvo Veskimets. The discussion focuses on how the economy affects the Baltic Sea.

In the second half of the day, Robert Hall from the Baltic Sea Transparency Cooperation reveals The Reasons for Continued Baltic Sea Degradation. Panel discussion Business Affecting Nature is held, where voice of the people get engaged. Participants and viewers from online will be engaged to discussion, sharing there views and experiences of Baltic Sea situation and business as usual.

At the end of the day the Baltic Sea Manifesto is adopted.

The event is moderated by Farištamo Eller and Madis Vasser.

The conference is free of charge and will take place in Lennusadam, 6 Vesilennuki Tee at Tallinn Seaport Harbour. The event starts at 10 a.m. local time (8:00 CET)

Through seminars and future collaboration we create a network to protect our shared and precious sea.

While European and national programmes promise ecological improvements of industries and water treatment plants around the Baltic Sea, the reverse is happening. The sea continues to be contaminated due to emissions from excessive nutrient loads and hazardous chemicals.

No appropriate control by civic society is in place; local and national authorities remain indifferent to the violations, and international regulatory authorities fail to exercise their control. In response, we aim to develop an international civil society organisations, as well as research and independent media. The aim being to organise channels for trust-worthy exchange of information and best practices, in order to strengthen civic pressure over the polluting industries.

The common challenge

During the last 15 years, EU and national governments have been funding the ecological optimisation of industries and water treatment around the Baltic Sea to reduce its contamination. Yet, due to different types schemes, business as usual and sometimes even corruption, industry have been discharging excessive nutrients and chemical substances into the Baltic Sea.

For instance, transnational projects to construct water treatment facilities took place between Lithuania, Poland, and Russia. However, monitoring detected that wastewater quality did not comply with the standards. The reason was traced to corruption during construction and maintenance. The results were published in media (2015, 2019), but the authorities’ response was limited.

Estonia faces a similar challenge. Although legislation is in place to regulate emissions, multinational companies continue to contaminate the sea. Despite efforts of local activists to expose environmental crime, the public authorities’ action remains limited due to conflicts of interest and lobbyism at national and local levels.

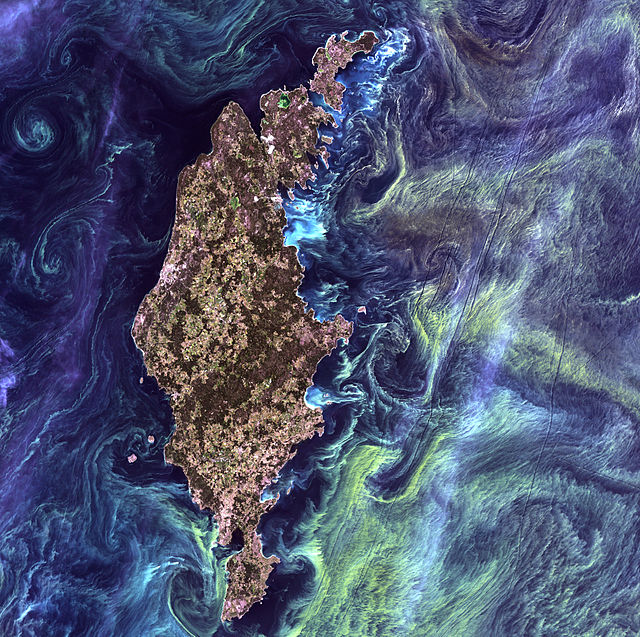

Sweden has a low level of perceived corruption, yet also discharges nutrient and chemical loads into the sea. On Gotland, municipal wastewater treatment aims to follow EU directives but is not able to meet them. Inspection of public sewage plants is inappropriately handled by municipalities, and mining and lime quarries are currently the largest contributor to the Sea contamination. In 2020 a release of iron sulphate from an 1800 ton shipment was reported; the spill was unreported and later played down in media.

While Baltic Sea countries faces different challenges, same patterns of environmental violations take place all around the region and lead to contamination.

Common challenge

- Water treatment and industrial facilities release contaminating substances into the sea while receiving funding for environmental improvements;

- Different types of corruption take place and authorities remain indifferent and downplaying risks;

- Weak engagement of civic society and absence of a stable channel for transnational action.

Transnational context

The EU Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region includes 12 countries in the Baltic Sea basin. National efforts to manage the shared body of water and its ecosystem are dysfunctional. National strategies have historically been clashing, calling for intergovernmental platforms such as EUSBSR and HELCOM. According to EUSBSR, “better coordination and cooperation between the countries and regions is needed to address these [EUSBSR] challenges”. In 1992, HELCOM compiled a map of “hotspots” – industries and municipalities that pollute the Sea with wastewater due to lack of treatment facilities or technical flaws caused by obsolescence and/or wear out. The HELCOM map included 162 hotspots located in 9 BSR countries; in December 2020, 122 hotspots were removed from the map, and reported as resolved. However, independent media and environmental organizations around the region regularly report cases of contamination of the Baltic Sea.

These intergovernmental platforms recognise the need for a transnational joint action. Yet, the regional strategies do not ensure on-the-ground transnational work by civil society. The plan for improving the situation cannot be limited to the construction of new treatment facilities and the modernization of existing ones. Joint actions should include a further monitoring of the plants’ operation by both public and civic actors to prevent various types of malpractices. The situation also proves that transnational pressure is more effective than the work of single national environmental NGOs.

Uncoordinated attempts by civil society organisations in the region have shown that it is almost impossible to address the challenge and organise effective civic and public control and pressure locally, as well as on a national level. Collaboration of public and civic stakeholders, appropriate pressure, and a stable platform for exchanging information, international expertise and best practices, can lead to improvements.

(SWE)

(RUS)

(SWE)

For more information:

info@ktu.ee

balticseatransparency@suderbyn.se